I should not be writing this. One is not supposed to proselytise about the joys of meditation and convert others to the cause. I know this and I understand why. Mindfulness and meditation are not the quick fixes that we read about in every magazine, nor are they a cure for all ills (at least not in the way most of us will interpret that); they are ancient, spiritual practices that take a lifetime to master. And even then, the prize of enlightenment is not guaranteed.

So why am I still typing? Well, because for me, at least, it has brought so much to my life that is good. It has provided me with a safe place to rest whilst the storm of the last few years has raged about me. It has guided me through some pretty scary waters and been a constant and steady source of light in the darkness. And no matter what happens to me in the future; its challenge and comfort will always be there.

I began meditating some time before my MS diagnosis, as a way of coping with chronic back pain and anxiety about my family. At first I did those five minute guided exercises from the internet and found it incredibly difficult. Because, as I discovered, mindfulness/meditation is not emptying the mind, as it is popularly conceived to be, but focusing it. Focusing on whatever it is that is your object and resisting the urge to make up a shopping list, daydream, worry etc.

As my practice and reading progressed, I also learned that it is about listening to yourself, accepting yourself and allowing thoughts to come and go without giving them too much attention. It is, in brief, about becoming present to the present moment.

Photo by Yuliya Ginzburg on Unsplash

With my MS diagnosis, things became a little more urgent. By then, I had been attending an excellent meditation class with a wonderful teacher, but travelling there was becoming difficult. So I had to find another way.

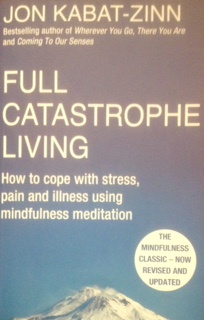

I had been recommended a rather heavy book that dealt with living with chronic health conditions and used mindfulness at its core. This was Jon Kabat-Zinn’s Full Catastrophe Living. It took me a while to read the 600 odd pages, but perhaps that was good preparation for what was to come.

His main recommendation was that you spend forty to forty-five minutes every day for eight weeks doing some form of meditation: body scan, yoga, breathing, etc and that this would seriously reboot your brain. I committed myself to doing it (I wasn’t capable of doing a lot else at the time!) and it certainly did something. No, I was not instantly enlightened, nor a better or superior person, but there was a shift in what I will call my consciousness and I have never looked at the world quite the same way since. Of course, any practice must be maintained, and though I confess to not always doing my forty-five minutes formal meditation, I aspire to doing a great deal of informal and some formal every day.

As with everything it seems, meditation practice is a paradox.

The goal of no goal

‘To bring calmness to the mind and body requires that at a certain point we be willing to let go of wanting anything at all to happen and accept things as they are and ourselves as we are with an open and receptive heart. This inner peace and acceptance lie at the heart of both health and wisdom.’ Jon Kabat-Zinn

This ‘inner peace and acceptance’ are at the core of any healing powers of meditation. As we sit in stillness, our minds get a break from the frantic stress of illness and as we learn to accept our situation, we also learn not to fight our struggling bodies, but to love them – imperfections and all. When we can do that, our frustrations melt away and our joy at simply being alive, at this moment, come to the fore.

Have I cracked this? No, of course not! I have good days and bad days. There are times when I am able to still my mind for only a few seconds and others when I happily drift in the womb of consciousness for a few minutes. But as quoted above, the outcome is not the point. The point is to turn up: to engage in the practice and keep bringing the mind back to the present. It is a reminder, over and over, that we live in the now and that memories of the past or fears of the future are no more substantial than a dream.